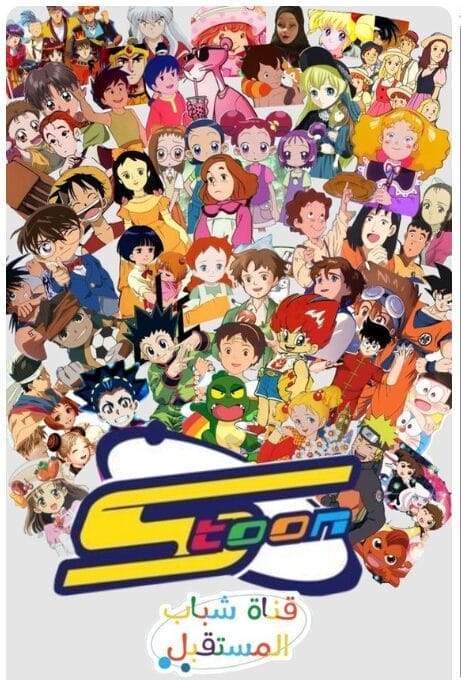

For millions of kids coming of age in and around the Middle East and North Africa in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the dinnertime ritual was familiar. The mad sprint home from school, the grab for a snack, and the swift, tactical takeover of the living room television. The remote control was set to one channel —whether it was Nilesat 116 or the familiar 32 on our local cable box—and when the clock reached a certain hour, a familiar, upbeat theme would boom from the speakers: the theme of Spacetoon. This was no regular TV channel; it was a gateway. It was our gateway.

Long before the era of streaming channels and real-time simulcasts, Spacetoon introduced an entire generation to the vibrant universe of Japanese animation. But its secret power wasn’t in the anime it broadcast; it was in its fearless, groundbreaking venture of Arabization. This was not translation; it was a matter of cultural alchemy, transforming distant Japanese fables into stories that resonated as our own, deeply and indisputably. The journey from those cleverly made dubs to today’s world of raw, instant subtitles is more than the history of media consumption—it’s a story about how a unique, pan-Arab cultural identity emerged in the glow of the television screen, and how its cultural legacy continues to resonate today.

The Bridge: Spacetoon‘s Grand Localization Project

Spacetoon debuted in 2000, arriving just as satellite TV was opening up new media horizons across the region. A young, rapidly growing population was hungry for more than the limited diet of dated reruns and educational shows; they craved modern, serialized stories with compelling characters and high stakes. Spacetoon, however, was more than just a distributor of cartoons; it was a meticulously crafted cultural world. Its programs were skillfully arranged into themed “Planets” (Adventure Planet, Sports Planet, Comedy Planet), giving children a sense of structure and community, a miniature cosmos they could visit every afternoon after school.

The true brilliance of the channel, however, was its commitment to cultural localization—a process media scholars define as the adaptation of a media product’s values, references, and humor to fit a local audience’s cultural context. Spacetoon masterfully achieved this through three key pillars: the art of the dub, the pragmatism of censorship, and the creation of a new musical soundtrack. These elements combined to create an anime experience that felt not just imported, but authentically Arab.

The Art of the Dub: Finding an Arab Soul

The Arabic dubbing alone was a spectacle. This was no production of voice actors cobbled together at the last-minute, reading literal translations. It was a form of art. Legendary voice actors such as Nada Shaher (Sailor Moon’s original voice) and Bassam Matar (the actor behind Detective Conan and countless others) did not just read out words; they gave rise to characters with a distinctly Arab touch. Local expressions, colloquialisms and terms of affection were present yet moderated to a certain extent to ring true across the dialects whilst maintaining the Modern Standard Arabic as a universal core. A greeting of “Marhaba!” or an exclamation of “Ya Allah!” might seem a small thing, but it was revolutionary. It presented Conan Edogawa and Usagi Tsukino as less distant, foreign protagonists and more as familiar next-door neighbors. This thoughtful dubbing created a close, familial relationship which raw subtitles could never aspire to have for a young, formative audience.

The Censorship Conundrum: The Price of Admission

Spacetoon operated within a certain socio-cultural environment, one calling for a notorious, and now nostalgically joshed-about, censorship policy. Romantic scenes, particularly kisses, were typically trimmed or excised.

Revealing costumes, like those in Sailor Moon, were digitally retouched with added sleeves, higher necklines, and longer skirts. Sudden alcohol, violence, or occult content was softened or entirely excised—typically leaving comedic inconsistency, like characters being shocked by an evidently empty glass that used to be a beer. While modern-day purists might cringe at such adaptations, one must consider their original purpose. This censorship was not so much about limiting as it was about permission. It was the magic key that unlocked millions of conservative living rooms.

Cleaning the material up to comply with local mores, Spacetoon made anime palatable to parents and censors, allowing these stories to make it into homes that would otherwise have deemed them off-limits. The censorship, in effect, was the price of admission one had to pay, and it was one that an entire generation paid gladly to access these magical worlds.

The Musical Makeover: The Shared Soundtrack of a Generation

Arguably, the most memorable and enduring part of the Spacetoon experience was its music. The channel famously and completely replaced the original Japanese opening and closing themes with extremely catchy, commissioned Arabic songs. They weren’t translations; they were complete reinventions, expressing the spirit of the program with original Arabic lyrics and melodies. It’s impossible to overstate the cultural impact of these anthems. Who among that generation will not remember warbling the boisterous, rallying choruses of Captain Majid (Captain Tsubasa) or the gentle, sentimental ditty of Sally (Princess Sarah)?

These songs ruled local music charts, were chanted in schoolyards, and became the shared sonic environment of a generation.

They took kids from Morocco to Iraq, from Syria to Saudi Arabia, all together in one, sing-along culture and created something rich, pan-Arab cultural reference point that transcended national boundaries.

Anime Through an Arabic Lens: The Theory of Glocalization

To the child, all these huge changes were unseen. The Dragon Ball Z sagas were still thrilling, Sailor Moon was still magical, and Detective Conan was still smartly puzzling. The deeper narratives of friendship, strength, and good overcoming evil penetrated. Yet, looking back, the dubbing and censoring created a genre of anime that was unmistakably and uniquely Arabized. In cultural theory, it has been most accurately termed “glocalization” — the blending of global cultural goods with local values, expectations, and traditions. Spacetoon‘s anime was not a “less authentic” watered-down product; it was an innovative, hybridized cultural product. An Arab anime experience. Romance was sublimated into deep friendship, and violence was presented in an overt moral binary. This was not watering down; this was repackaging.

It placed these Japanese stories in a cultural and ethical framework that resonated deeply within Arab family and societal life. Spacetoon, unwittingly or not, presented anime not only as entertainment but as a medium that conveyed and advocated for universal morals—cooperation, honesty, compassion, and justice—now framed in a familiar, acceptable context.

The Legacy: From Shared Nostalgia to Modern Fandom

Decades later, what remains most striking is how deeply those glocalized shows embedded themselves in the collective identity of a generation. For the “Spacetoon Generation”, these programs were more than cartoons; they were cultural pillars. They provided a common language and a shared set of references for millions who otherwise had few unifying pop-culture moments. This shared nostalgia has become a powerful cultural force in the digital age.

Compilation videos of the original Arabic openings on YouTube rack up millions of hits, serving as a time machine for fragmented diaspora communities and native citizens alike. Social media sites and internet forums are filled with memes about the curious censorship, with users fondly recalling, “Remember when they substituted all the beer with soda?“ It’s not a childhood nostalgia for cartoons; it’s a nostalgia for a homogeneous, collective childhood experience—a valuable and precious thing in a region oftentimes divided by war and politics.

Most importantly, the generation of Spacetoon now constitutes the leaders of Arab anime fandom today. They are the fan subbing communities, the YouTube and TikTok writers, the organizers of large comic cons like Middle East Film & Comic Con and Saudi Anime, and the artists flooding social media with webcomics and fan art. Their innate love affair with the form, initially fueled by those carefully curated afternoons of watching television, has become an informed, passionate, and globe-straddling community. When access to fast internet became widespread, most of these viewers embarked on a process of rediscovery. They turned back to their childhood programs in their “original” uncut, subtitled form. It was culture shock for some: the violence was more brutal, the love stories more adult, the philosophical concepts gloomier and more complicated.

But to most, fondness for Spacetoon‘s less violent, locally adapted versions never faded.

It created a specific dual identity. They now possess in their minds two versions of the same story—the universal, “true” Japanese one and the cherished, sentimental Arab one—and both coexist together, framing their enjoyment and identity to some extent.

Why Spacetoon Still Matters: A Challenge to Cultural Flow

In traditional media studies, histories tend to be a one-way cultural flow from the “core” (cultural centers like Japan or the U.S.) to the “periphery” (consumption grounds like the Middle East). Spacetoon‘s pedigree deliberately challenges this simplistic framework. It was not a passive recipient but an active, transforming force. It did not simply broadcast content; it incorporated, translated, and re-engineered it into a new product that best resonated with an Arab kid’s heart. That’s significant because it suggests that international fandom is never unified. It’s a multiplicity of divergent, localized fandoms.

How Arab kids loved Sailor Moon or Grendizer is different culturally and contextually from how kids in Japan or Brazil loved them—and that difference is not a deficit. It is a sign of the resilience of storytelling and cultural translation. Our Spacetoon generation did not just view anime; we produced with it a culture, one that today impacts arts, media, and community involvement in the area.

Kids these days have the world of anime at their fingertips—unedited, unfiltered, and live along with the rest of the globe. For those who grew up with Spacetoon, there is an indelible, unique bond we retain. It was not merely a channel; it was a cultural bridge, a shared school of imagination, and for all of us, the initial introduction to the understanding that stories could be magnificent and transcend languages and borders, be ingested and recreated, and feel as if they still belonged to us and us alone. Even now, the initial sounds of the time-honored Arabic opening theme of Detective Conan or a Grendizer figurine in a shop window can induce a profound wave of wonder from childhood. It is living evidence that a brightly colored channel from our youth did a great deal more than shape our viewing habits; it defined a generation’s sense of wonder, belonging, and identity.

From Spacetoon to Subtitles: How Arabic-Dubbed Anime Shaped a Generation – Amal Hasan