(Author: Patricia Baxter)

Content Warning: The following article discusses depictions of ableism directed towards neurodivergent individuals, in both fiction and reality.

Table of contents

Change is a constant part of life. The seasons continue to cycle, plans change at the last minute, and people learn and grow from their experiences. Being an autistic woman, I have experienced both the positive and negative sides of change, one of the most welcome being how the world is slowly becoming kinder to neurodivergent people. When I was diagnosed, the world was a different, less empathetic place for our community, and the media being made at the time reflected those attitudes. Now, we are seeing a cultural shift in how neurodivergent people are being perceived, with artists using comics as a way to discuss their personal experiences becoming the norm, and authors accepting their characters being read as autistic by their readers and peers.

Among these great changes are the diverse ways in which topics that resonate with neurodivergent readers are now being treated with empathy and respect, such as social masking. Social masking, or masking, refers to neurodivergent people hiding their emotions, symptoms, interests, and personal behavior such as stimming and vocal repetition, in order to appear “normal” by neurotypical society. This can be done for a myriad of reasons, but the most common include attempting to “fit in” so that we can integrate into a social environment, whether it be a workplace or friend group, or to protect ourselves from ableist violence. This is comparable to closeted LGBTQ+ people passing as cisgender heterosexuals, in an attempt to protect ourselves from people who may do us harm and maintain a livelihood. Masking takes a lot of energy to maintain, which is difficult and draining to achieve even for able people, so it is especially taxing for disabled people.

While my own experiences have not been as extreme or negative as other neurodivergent peers, I still practice different types of social masking in aspects of my life. One of these methods has included not discussing my interests when being introduced to a new social setting. In the past I have encountered instances of being bullied for my interests in “childish” media, and as such would not discuss them for fear of a repeat of these negative experiences. I do not feel ashamed for what I like, but being shamed by others is an event that stays with you. Various recent manga series cover characters encountering shame and social pressure to hide their passions to limited standards of “normal,” which resonated with me as their stories resembled my own life in different ways. Thankfully, each character in these narratives is also able to achieve their own happiness, and continue to pursue the things they love, which is empowering to witness as a neurodivergent reader. Through these works, I’ve explored and analyzed these instances of social masking, how it resonated with me, and how these stories can have a positive impact on readers.

The Long Term Impacts of Social Masking in Box of Light

Seiko Erisawa’s Box of Light is a supernatural manga about a convenience store located on the boundary between life and death, where customers are people dangerously close to passing on. The fifteenth chapter of the series, “Reminder,” focuses on a woman named Sotoba, who appears to be a model employee at an architecture design firm, by always offering to help her coworkers and completing every assignment efficiently. However, this is just a facade that she has created so that she can “[Appear] like a proper adult,” but admits she is also “Struggling to move from faking it to being it.” Additionally, she has stopped herself from doing certain behaviors, such as her nervous laugh, because she does not want to continue being her self-described “weak, wishy-washy, useless” past self from her previous job. As a result, Sotoba pushes herself beyond her limits to mask as a reliable and efficient employee, which is part of the reason why she winds up in the convenience store on the boundary between life and death.

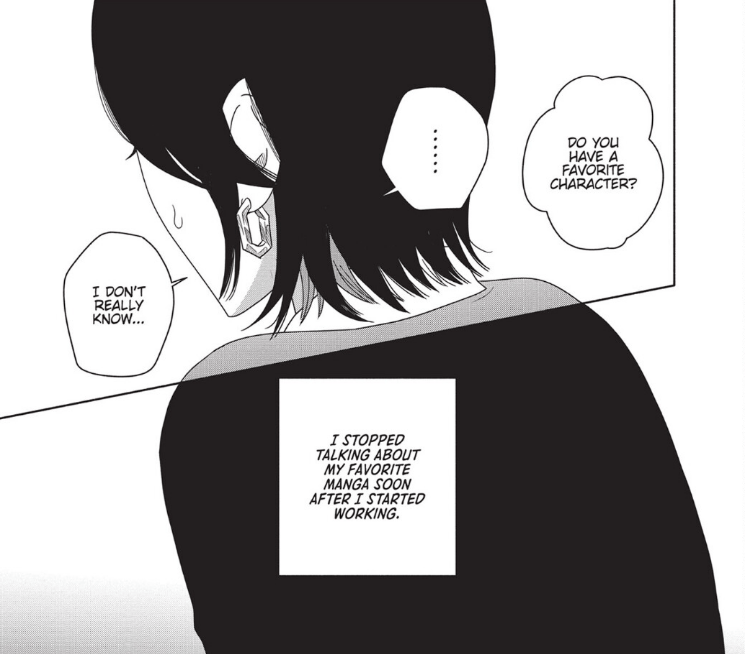

On top of these numerous instances of masking in Sotoba’s work life, is hiding her love for the manga Canelé Academy, a series that she has been reading since junior high school, and never fails to pick up the newest volume on release day. Her passion for the series, its characters, and stories, are so great she calls the manga her “guiding light” in life. However, upon entering the workforce, Sotoba had a negative experience which led her to hiding her interest from others. During a team building exercise, a co-worker accidentally took Sotoba’s phone, which had a Canelé Academy lock screen, and gave a visceral disgusted response to the image. While the co-worker apologized, the damage was done, and Sotoba made her lockscreen a gradient image immediately afterwards. As a result, Sotoba keeps her passion for Canelé Academy a secret, so that she does not risk being mocked or hurt for enjoying the manga she loves.

Thankfully, Sotoba finds another passionate fan of Canelé Academy working at the convenience store, who helps her try to find the newest volume of the manga. This results in the woman reflecting on the series, and what a profound, positive impact it has had on her life for over a decade. Renewed by her love and passion, Sotoba is able to return to the world of the living, and discovers that one of the juniors at her workplace is also a huge Canelé Academy fan. As a result of this, Sotoba begins to live her life as her honest self, only taking on a reasonable number of tasks and no longer hiding her passion for the manga series that has positively impacted her life.

Sotoba’s experience here resonates a great deal with me, as I have also experienced being bullied for the things I am passionate about. For many neurodivergent people, especially those on the autistic spectrum or with ADHD, having very specific things we are interested in, commonly referred to as a special interest. With my friends and on social media, I make it very clear that I am passionate about animation, comics, and video games, but in the workplace, I commonly hold myself back from talking about them, for fear of being mocked. This comes from multiple instances of being bullied for my interests, one noticeable instance being a cohort from my graduate studies mocking me for enjoying animated films in front of the rest of our peers. They never apologized, and the feeling of shame associated with the experience made me reluctant to talk about the things I enjoy, both in school and in the workforce. Thankfully, I have been able to find ways to open up and talk about my interests once I feel comfortable, and have been able to make good connections because of them, but the fact that I still feel that invisible pressure to “default” to holding back is something that frustrates me.

Sotoba’s story demonstrates the negative impact that long-term social masking can have on a person, both in terms of trying to prove our worth in the workplace and the ways being shamed for enjoying “atypical” interests last long after the initial event. Repressing her authentic self was so damaging that she nearly lost her life in the process, which, in many ways, is a fantastical demonstration of how constantly masking negatively impacts neurodivergent people. By always trying to portray the best version of ourselves to others, it becomes difficult to ask for help as it may result in being perceived as “weak” or “a burden.” Furthermore, hiding our interests results in feeling disconnected from our authentic selves and what really gives us joy in life. Thankfully, Sotoba was able to re-discover her guiding light, and resolved to never lose it again. With many stories of adulthood focusing on “growing up” past our “childish” interests, it is delightful to see a narrative that instead reaffirms that our passions should not be mocked and ridiculed even if they aren’t “conventional.”

Resisting the Pressure to Conform in Takahashi from the Bike Shop

Arare Matsumushi’s Takahashi from the Bike Shop is a slice-of-life romance manga focused on the life of Hanno “Panko” Tomoko, a thirty year old office worker who is constantly bullied and pushed around at work. While she thankfully has one close friend who sticks up for her and knows her authentic self, the rest of their co-workers and supervisors push extra tasks onto Panko, and ignore her personal requests such as asking for an alternative to beer at an office party. Socially, Panko finds herself struggling to keep up her childhood friends’ lives and her mother’s expectations of what it means to be an adult woman. Still, Panko continues to live her life, enjoying herself by watching anime and genre films like Kick-Ass, eating good food, and generally living happily as her authentic self during her personal time.

Even so, Panko still encounters pressures to conform to societal expectations. One major example of this is when she is invited to go on a movie date with a co-worker, Yamamoto Kouki. After being asked what she wants to watch, Panko says she wants to watch the new Doraemon film that was recently released. Her date is shocked and laughs at her choice, assuming she was joking, and pressures her to watch a romantic tearjerker that she has no interest in watching due to the subject matter and over two hour running time. She manages to sit through the majority of the film, albeit very bored, until Kouki turns on his smartphone during the film with intensely bright light shining. Frustrated at her date’s rudeness, Panko leaves the theatre and comes across her friends in the lobby, who have just finished watching the Doraemon film. After talking with them, Panko breaks down in tears and confesses that she really wanted to watch the animated film, but having her choice mocked by Kouki made her feel stupid, and his rude behavior in the theatre made her angry. Thankfully, her friends have her back on both points, with one of those friends, Takahashi Ryouhei, going as far as getting genuinely angry on her behalf.

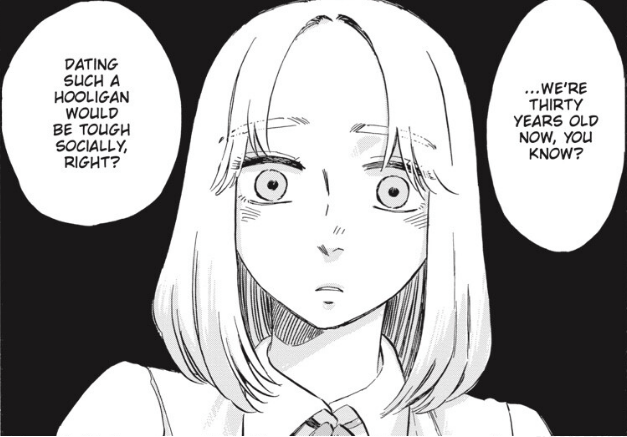

Later, after Panko and Ryouhei begin dating each other, Kouki approaches Panko and tells her that it isn’t a good idea to be dating a “hooligan” since her social image will be negatively impacted, and implies that Ryouhei is merely taking advantage of her kind nature. At this confrontation, Panko gathers up her anger and frustration at Ryouhei being insulted, along with her own personal hurts, and tells Kouki off, culminating in saying that “[Ryouhei would] never mock anyone or what they like in a million years.”

Panko’s character growth resonated with me, as it reminded me of the many trials and tribulations that come associated with adulthood and being pressured to present oneself “appropriately.” While I have been able to take steps to stand up for myself, and my interests, the power of the expectation to conform is always present. Like Panko, it is important to remember that compartmentalizing yourself for the sake of other people’s image of you is not what will make you happy in the end. The friends and companions I have made over the years are all very dear to me, and I owe those connections to being honest about myself and never shying away from what I care about.

Panko’s personal journey demonstrates the various different ways people are pressured to socially mask and conform, and also how rewarding it is to find loved ones who genuinely appreciate us for our authentic selves. Panko was used to being dismissed by the majority of her co-workers, since it made her life “easier” even if it didn’t make her happy. However, with the support of friends, old and new, and a partner who all love and respect Panko for her passions and interests, leading to her standing up for herself and the people she loves. This will no doubt be a continuous journey for Panko, as it is for all of us, but with the help of people who genuinely care for her at her side, it will always be worth the effort.

Childhood Social Masking in Spacewalking With You

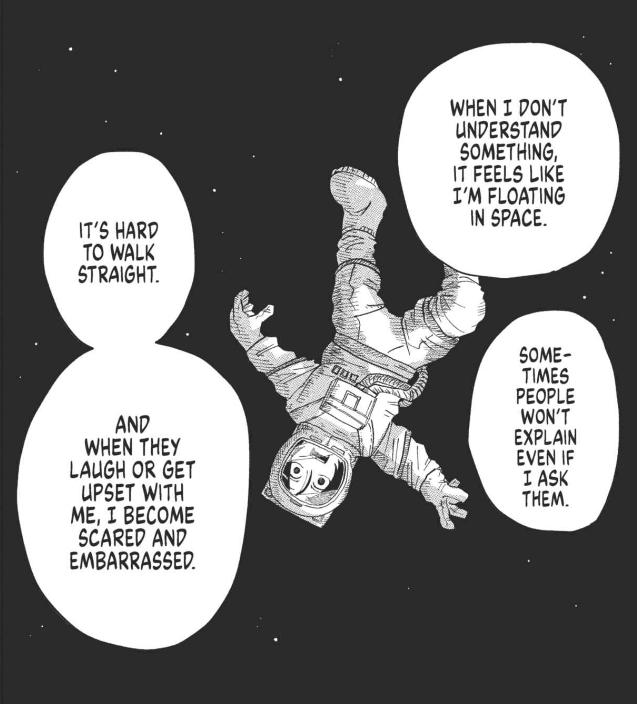

Inuhiko Doronoda’s Spacewalking With You is a coming-of-age manga focused on the daily lives of two high school students who are neurodivergent boys struggling with learning disabilities. One of these boys, Uno Keisuke, the series’ deuteragonist, is heavily implied to be on the autistic spectrum, as he showcases various common traits such as inability to read social cues, extremely literal thinking, and difficulty prioritizing tasks among other behaviors. Uno compares these confusing parts of navigating daily life to “floating in space,” leaving him metaphorically adrift in a world where the rules are not always clearly defined. Thankfully, he has an essential “tether” in the form of a notebook which helps him navigate through these confusing forms of his life. It includes instructions for how to ride a bus, what to do when he’s feeling overwhelmed, and how to interact with his peers.

Another core aspect of being on the autistic spectrum is having an intense level of interest in one or multiple topics, which can be showcased through extensively researching the topic and collecting objects associated with our interest. In Uno’s case he loves space and astronomy, having several space themed items in his bedroom such as an astronaut alarm clock and Saturn-kun plushie, and his older sister recalling him extensively reading a book about space when they were younger. Another common trait amongst autistic people is “info-dumping” about our passions, as talking about the things we love with the people we care about is a way of forming deeper connections. Unfortunately, these levels of passion are perceived as abnormal by many neurotypicals, and as such many autistic people find themselves being bullied or ridiculed for our interests.

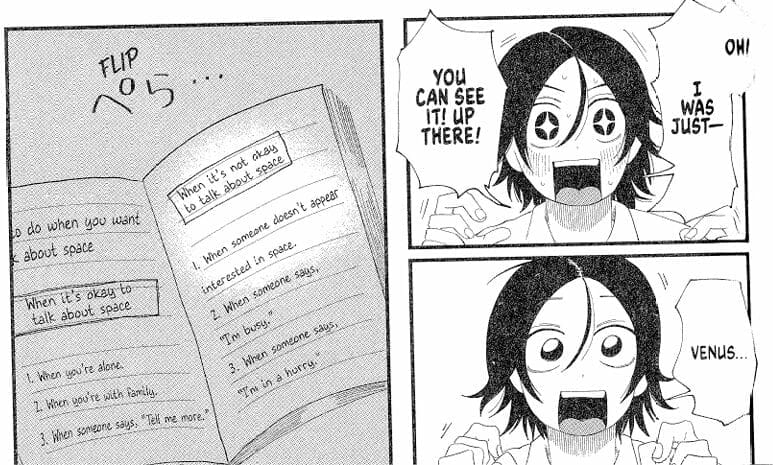

Sadly, Uno has also experienced similar negative comments from neurotypical people, as evidenced by the sections in his notebook telling him when it is and is not appropriate to talk about space with people. Upon seeing Venus in the sky, Uno is overcome with the urge to tell his new friend, the protagonist Kobayashi Yamato, about the planet, but stops himself when remembering the relevant page in his notebook. Thankfully, Kobayashi is able to notice Uno’s desire to talk, and tells him he is willing to listen, prompting the boy to info-dump about Venus, and answers Kobayashi’s questions about the planet. Later, when trying to sign up for their school’s Astronomy Club, Uno learns that the club is at risk of being disbanded since they have less than three members, since Uno would only be the second member. Kobayashi assumes that Uno will ask him to join, but is surprised to find that his friend does not do this. When asked about it, Uno consults another page of his notebook about interacting with classmates, a tear-stained page saying that he shouldn’t force them to do things, even if he really wants to do an activity. With this information in hand he tells Koyabashi, “I think I’d be bothering you if I asked you to join… so I won’t ask!”

While it is always important to ensure everyone is on board with an activity, Uno’s experience here shows that he, like many neurodivergent people, has learned from a young age how to mask his interests so that he does not “inconvenience” or “bother” other people, which is something that I am also deeply familiar with. From a young age, I noticed that it was difficult to talk at length with my peers on the things that I was interested in, making it hard to forge friendships. However, the worst example is a relative stating that I was “forcing” my younger siblings to spend time with me, which caused me to second guess my wishes to spend time together with them through playing video games or watching anime. Thankfully, the love and friendship my siblings and I have for each other is much stronger than that distant relative’s hurtful assumptions, and we all share our passions openly and proudly with each other. Even so, the fact that this insecurity and pain was able to take hold inside of me from a young age, speaks to the many ways neurodivergent children are shamed into hiding themselves away, much like Uno.

Thankfully, Uno also has a good friend at his side who is ready and willing to listen to him talk about his interests. Kobayashi was able to see the pain that Uno was hiding away behind his social mask, and knowing how passionate his friend is about space, correctly assumed that Uno really desires making connections with likeminded people. Kobayashi insists that he is willing to join the club, and if Uno ever needs help all he has to do is ask his friend, giving him a new page to add to his notebook as proof of this promise.

Uno’s story demonstrates that the pressure to social mask can begin at a young age, as well as the emotional toll that hiding ourselves and being perceived as a “bother” gradually has on a person. Thankfully, Uno has family and friends who love and appreciate him for his authentic, space-loving self, rather than a mask he has created to navigate through life. Furthermore, he is encouraged to use tools, such as his notebook, that help tether him to accomplishing daily tasks in life, rather than shamed for needing them. Seeing a narrative where a neurodivergent child is able to go through life and experience people who love and respect him for his authentic self, is amazing to witness. Narratives like this are extremely powerful and beneficial for neurodivergent children to see, and it gives me hope that more kids are able to grow up knowing that they will find friends who support, respect, and love them.

Conclusion

Witnessing the gradually changing media landscape to include neurodivergent stories has been a real joy to witness in these past few years, especially stories that encourage the characters to live as their authentic selves. Growing up in a landscape where I was continuously pressured to conform to “normal” interests, and appropriate levels of expression, I am glad that we are beginning to see narratives that no longer shame people like me. While there are many hurdles in the way in reality and fiction for these types of stories to become the norm, the fact that we are already seeing the change occur gives me hope that we will see more neurodivergent and disability-focused stories written with empathy. I look forward to seeing what that future holds, and that we are all able to find our tethers along the way.

Unmasking Neurodivergence in the Manga World – Patricia C. Baxter